Pallet System Software Boosts Cell Flexibility

The software running this shop’s newest FMS from Fastems adds a layer of automation that enhances the inherent flexibility, productivity and effectiveness of lights-out operation. Dynamic job scheduling is the key.

Article From: 5/14/2015 Modern Machine Shop, Mark Albert, Editor-in-Chief

“It’s like shuffling a deck of cards every day.” That’s how Paul Hogoboom describes the challenge of managing the ever-shifting job priorities that P&J Machining faces as a highly-competitive aerospace job shop. Mr. Hogoboom is president of P&J, located in Puyallup, Washington (35 miles south of Seattle), a company that he manages with his younger brother, Mike. Together, they are carrying on a tradition that started when their father founded the company 36 years ago.

Like their father, the Hogoboom sons have aggressively sought out advanced machining technology to stay competitive and profitable. This policy is evident in the shop’s long history of lights-out machining on flexible machining systems and palletized cells. The first of these automated systems began operation in 1997, the latest in 2014. In fact, comparing these installations shows the evolution of the cellular concept and the technology that supports it.

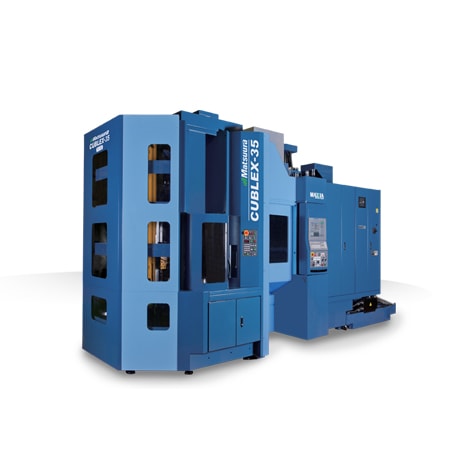

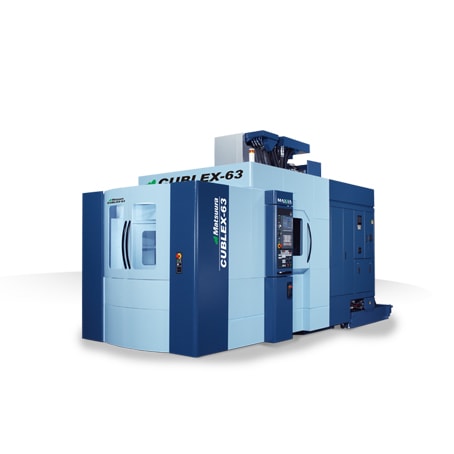

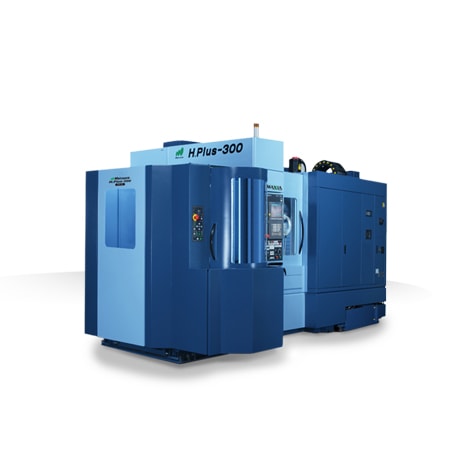

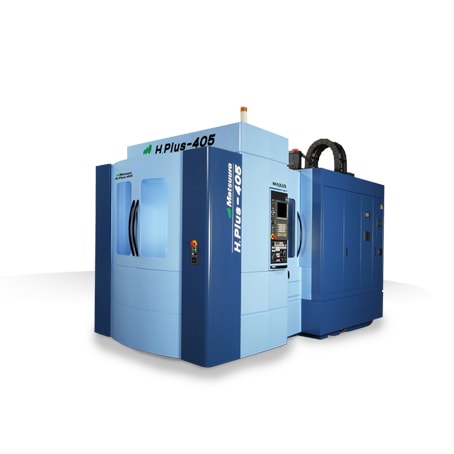

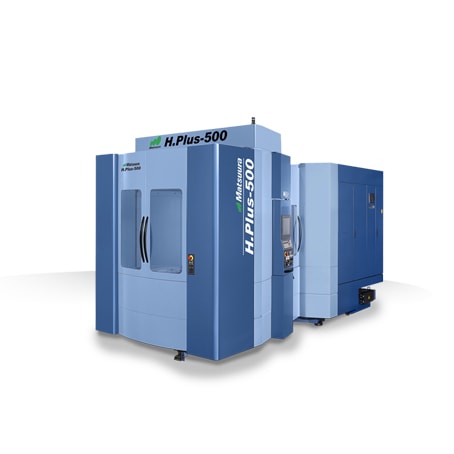

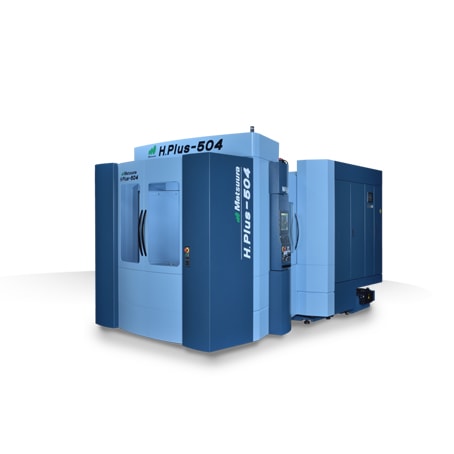

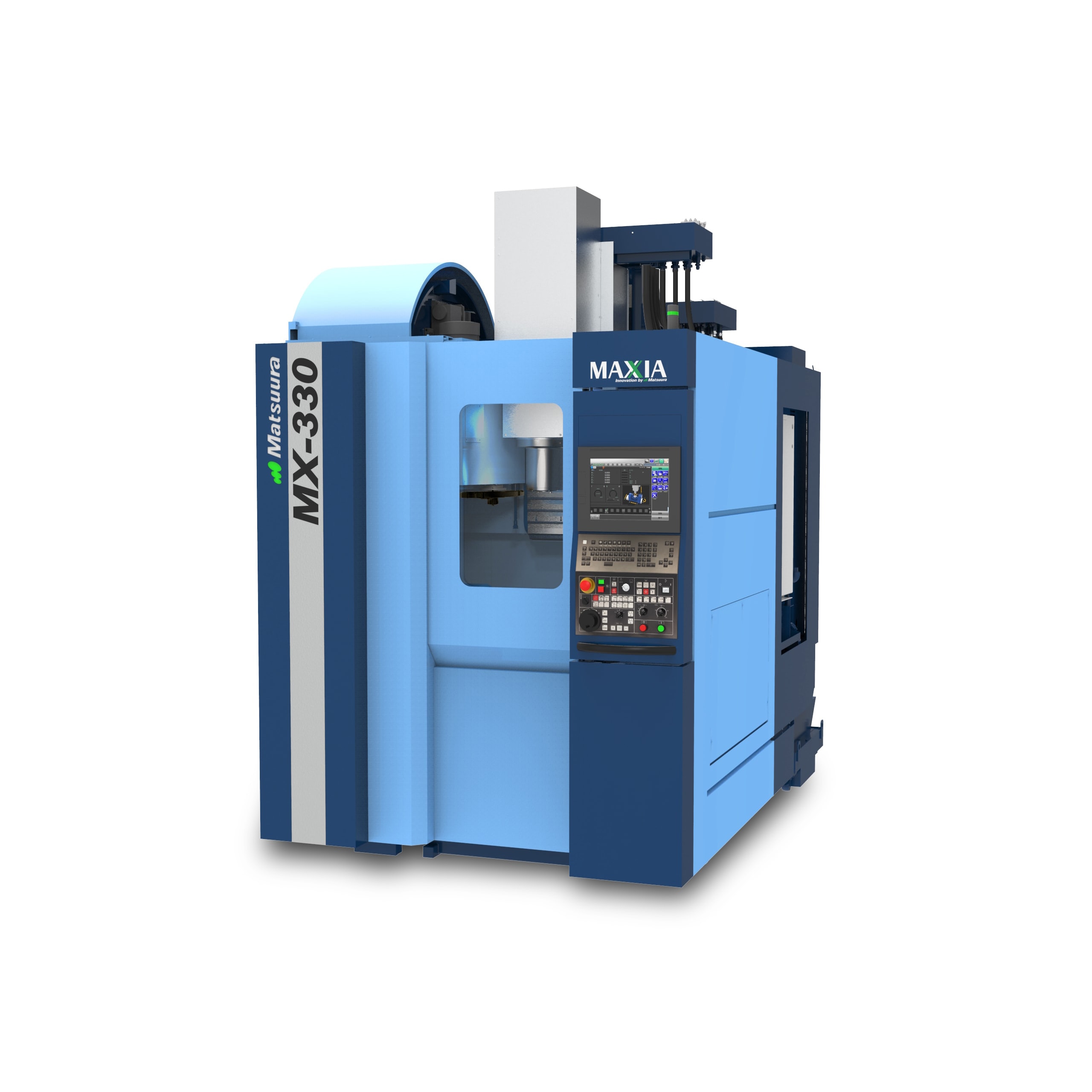

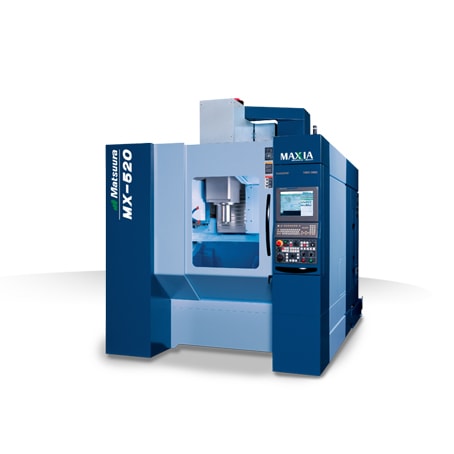

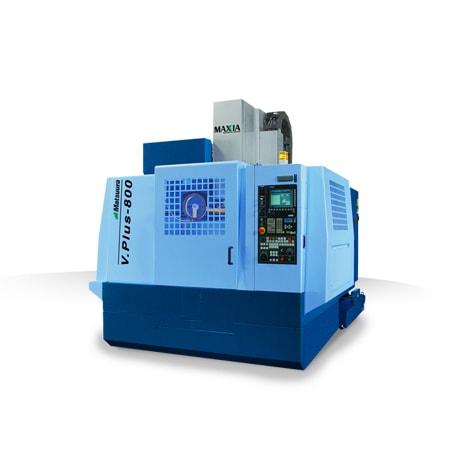

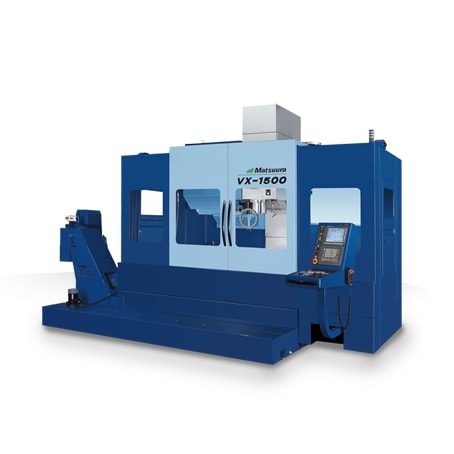

The newest system, which consists of two four-axis Matsuura HMCs with a Fastems pallet storage and retrieval system, represents what Mr. Hogoboom considers the most important advance in this sector of lights-out aerospace machining, namely, the control software’s capability to automatically reschedule job priorities on the fly based on shifting demands in production from customers. In short, the Fastems MMS5 cell control system determines the optimum sequence of workpiece pallets to meet the requirements of the customer’s aircraft “build forecast.”

This capability to “shuffle the deck” of job priorities stacks the cards in the shop’s favor, so to speak. Some of the major benefits of this software capability include improved flexibility of the system to manage 30 to 45 different part numbers in active production at any one time on the cell, better coordination of production timing to meet kitting programs that speed aircraft assembly at the customer’s plant, high in-the-cut times (97 to 98 percent) and streamlined dock-to-dock material flow. Keeping track of production details within the software also provides reliable traceability to comply with aerospace contracts.

Given its long experience with lights-out production, P&J was well-prepared to leverage the advanced capability of the new automated cell. Over the years, the shop has learned what planning, pre-engineering, staffing, training and day-to-day operational considerations have to be attended to in order to make unattended operation successful on any automated cell or system. All of these factors apply to the new system, with the addition of learning to take advantage of the scheduling, networking and machine-monitoring capability of the control software. Remote access to the system, for example, gives supervisors and top management the tools to monitor job progress, respond instantly to customer inquiries and interact well with the cell operation team.

“We are an aerospace job shop, not a production facility. Flexibility has to be combined with automation to be effective in a job shop environment,” Mr. Hogoboom insists. The dynamic scheduling capability of the Fastems control system provides that combination at a new level of efficiency and proves its value in today’s aerospace job shop settings, he says.

HMCs on the Horizon

Mr. Hogoboom summarizes the impact of cellular machining with palletized HMCs with this statement: The capacity of two palletized HMCs is comparable to that of 10 unpalletized VMCs. He bases this conclusion on the shop’s experience moving from reliance on vertical machines to the introduction of palletized horizontals and the transition to unattended machining on automated systems. The company’s roots go back to contract machining performed in the family garage in the early 1970s in the Tacoma area. In 1986, the company moved to a new building on the outskirts of Puyallup. At the time, its machining was entirely performed on VMCs. In the mid-1990s, Mr. Hogoboom became the manufacturing manager and began to explore horizontal technology, attention that was encouraged by his father, who was still active in company administration.

“We learned a lot about setup reduction, off-line tool prep and other quick-change techniques,” he recalls. But it became more apparent that the inevitable idle time inherent in vertical machining operations was a drag on profitable production, especially for many of the aerospace parts the company was bidding on.

Tours of local shops with automated cells built around HMCs convinced Mr. Hogoboom that the future of aerospace machining lay in this direction. The shop bought its first palletized HMC in 1997, although the cost of this investment (more than $1 million) gave his father some sticker shock.

However, as the shop became accustomed to horizontal machining and using the pallets to virtually eliminate idle time, the return on the investment became evident. More pallets were acquired, then a second machine was added, and then a pallet storage and retrieval system to serve both machines was installed. Along the way, the shop learned to become more organized and disciplined in order to begin lights-out machining (the only way to achieve the level of productivity that generates payback for these costly system, Mr. Hogoboom says).

Since then, the shop has added three more automated systems consisting of fully palletized HMCs. The recent installation of the Matsuura HMCs and the Fastems pallet system is the culmination of this trend to date. Installation of the system began in late 2013 in a building constructed two years earlier next to the original (but much expanded) facility at the Puyallup site. This cell, intended for aluminum aerospace parts, was in operation early the next year.

High on Palletized Automation

That new Matsuura/Fastems cell represents a number of firsts for P&J. It is the first installation in the shop to incorporate a Fastems pallet system. This is the first such system in the United States with Fastems’ 20-foot high racks for 500-mm pallets. The Matsuura H Plus-500 machines served by the pallet system are the first of this model of HMC in the United States from this builder.

The pallet system accommodates a total of 60 pallets and has two load/unload stations that are adjacent to one another. The HMCs are located side by side on the other end of the pallet system. There is ample access to the sides and rear of these machining centers. Pallets are stored, retrieved and delivered by a rail-guided stacker crane that travels the length of the system. The pallet rack has five levels with 12 stations on each level. The highest level is open at the top to accommodate pallets with unusually tall fixtures or workpieces that extend above the upright pedestals mounted on the pallets.

“We like the hardware of the Fastems pallet racks because they are sturdy and rigid,” Mr. Hogoboom explains. The racks can accept fixtured and loaded pallets weighing as much as 1,540 lbs. Powder coated steel trays under each pallet station collect coolant runoff and funnel it to pipes leading back to the central coolant system. In the unlikely event that a malfunction causes a runaway condition, the rail-guided stacker is protected from hard stops by a shock-absorbing buffer at each end of the line. The system can be expanded by extending the pallet racks and stacker shuttle track. Because the stacker receives commands via an optical infrared transmitter, there are no cables to limit the distance it can be extended.

Each of the Matsuura HMCs has a number of on-board automated systems that facilitate lights-out operation. The automatic toolchanger has stations for 320 tools, providing adequate room for all the tools and a number of duplicates to cover almost every operation required for the parts that go across this cell. A laser tool sensor checks that a tool delivered to the spindle is not broken or missing a component. A spindle-mounted touch probe checks critical features at the end of each roughing cycle and can feed inspection data to the CNC to adjust finishing parameters to ensure a good part.

Flexibility is in the Software

Mr. Hogoboom admits that all of the automated machining cells at P&J are capable of running unattended for 14 of the 24 hours in a day, with operators present for the remaining hours during the day shift to unload pallets of completed parts and reload them to keep the machines running virtually around the clock. The automated lines are shut down on Monday mornings only long enough to complete systems checks and scheduled maintenance. What sets apart this newest cell is the capability of the software system.

Control systems on the other cells are fine in that they do exactly what they are told to do ahead of time by cell operators. In other words, they are capable of exchanging pallets as work is completed according to the entered plan. The newer of these systems may send alerts by text message or email if unplanned stoppages occur. However, prioritizing, scheduling and routing the pallets are functions determined solely by operator input. If job priorities change due to scheduling contingencies, the work plans for the cells must be manually updated to reflect these shifting demands.

The software of the Fastems cell control system, in contrast, can manage this scheduling function on its own. It keeps track of jobs active in the cell and responds to part quantities and delivery dates received from the shop’s master scheduling and manufacturing resource planning (MRP) system. Based on this input, the cell software coordinates the activities to get the right parts in the right quantities done at the right time.

The activities that it coordinates include raw material deliveries to the load stations, loading the lineup of pallets (with appropriate fixtures) in proper sequence, and scheduling for available machine time based on priority. The software has the intelligence to return a pallet to storage if another pallet must go ahead to meet a revised delivery date. Upon its completion, the stored pallet is automatically reactivated to its position in the schedule.

“The beauty of this software is that it can respond to changes in part mix, part quantities and part due dates without additional planning by the cell team,” Mr. Hogoboom says. For example, if a delivery date for a certain quantity of parts is moved up, the system automatically reprioritizes the pallet sequence and machine assignments. Pallets with the “hot” job will go ahead of lesser priority ones—these pallets may be returned to storage to await open time at one of the machines later.

The system also manages machining resources within the cell. For example, the system checks that cutting tools required for scheduled work are in the ATC and that these tools have adequate cutter life remaining to complete the work. Missing tools or tools that will need to be replaced are flagged for operator attention.

One common situation that highlights the value of this flexibility is a late engineering release from the customer. These parts must be moved to the front of the line so that speedy delivery will help the customer catch up with the production schedule to prevent delays at the aircraft assembly line. Mr. Hogoboom reports that, on occasion, even a single part may have to move through the cell for completion during the day shift or next morning at the latest to satisfy the customer’s request. As these emergency jobs are completed, the cell software reactivates the standing schedule and makes adjustments to compensate.

Likewise, the relative ease by which the cell software can accommodate a work schedule that presents constant shifts in part types, lot sizes and due dates is an aid to P&J’s active kitting programs. A kit is a shipping container designed to hold all of the components required for a specific step in aircraft assembly. This container is delivered directly to the point of use at the customer’s assembly line, where assemblers unpack the kit as soon as it is needed. Because parts are received in pre-labeled trays or compartments, with related assembly instructions and checklists at the ready, kitting streamlines assembly, reduces errors, eliminates part shortages and sidesteps delays at the customer’s receiving department.

To participate in a kitting program, the supplier must commit to the discipline and organization it involves. For example, the delivery of kits has to be closely coordinated with the customer because the forecasted number and configuration of aircraft to be produced varies from month to month. P&J uses the customer’s production forecast to time kit shipments, and this timing must be reflected in the jobs scheduled for its machining cells. Keeping up with part production to meet kitting requirements is easiest on the Matsuura/Fastems cell, which Mr. Hogoboom attributes to its scheduling capability.

Internally, a similar benefit is enjoyed in raw material flow. Workpiece blanks are delivered to the machining cell twice a day based on type and quantity as indicated by the work schedule. Because this work schedule is regularly updated, these material deliveries are accurate and timely as a result, thus minimizing the staging of work in process at the machining cell. Machined parts coming off the cell move on to further processing just as promptly.

The Shop Does Its Part

Underlying the cell software’s ability to maintain schedules dynamically is the carefully developed production strategy that P&J put in place to accompany the installation of this cell. This strategy reflects the shop’s prior experience with cellular machining and lights-out operation. Mr. Hogoboom emphasizes that the success of an automated cell largely depends on key decisions made before it is configured and installed.

Here are some of the major steps that the shop followed to prepare for the Matsuura/Fastems cell.

1. Create an effective cell operations team. The right people for this team must have strong skills in machining and technology management, be open to new ideas and procedures, function well within a team, and be flexible in attitudes and expectations. The leader for this cell is Rick Nelson, a P&J veteran with experience in automated cell operation. A cell team usually includes a journeyman machinist, a programmer, the manufacturing manager, a maintenance person and the crew of machinist/operators assigned to running the cell during the day shift.

2. “Pre-engineer” all aspects of cell production. This step covers most of the decisions about how parts will be machined on the cell. It includes making decisions about the type and size of parts to be produced, the design of fixtures and clamping mechanisms, cutting tool provisions, and many other details. In this case, the cell is dedicated exclusively to aluminum workpieces, most of which would fit inside a breadbox. The majority of parts currently produced on the cell are wing-to-body components and interior structural parts for two long-running commercial jetliner programs. Approximately 700 different part numbers covering several broad families of similar workpieces can be produced on the cell, although 30 to 45 different parts are likely to be represented among the array in production on a typical day.

The 500-mm pallets, which are supplied by the machine tool builder, feature T-slots and bolt holes. Many pallets have an inverted T-shaped upright providing two sides on which to mount a variety of vises and other clamping devices. Each side may be fixtured for a different part or different operation. Orientation of the workpieces for each operation and the most practical workholding options are established together. An important goal in this aspect of the pre-engineering phase is to balance the variety of fixtures needed with capacity to meet anticipated order quantities.

Decisions about cutting tools also require balance. Although the capacity of the ATCs is ample, it is not unlimited. Both machines have identical tool inventories so that they are interchangeable for scheduling purposes; either machine can process any pallet. CNC programmers maintain the list of available tools and prepare part programs accordingly. The programming department also provides tool-life data so the cell control system can manage tool usage.

3. Provide complete and accurate documentation in a digital format. The availability of this documentation is essential to efficient pallet loading and unloading procedures. For example, as pallets of finished workpieces are unloaded at the beginning of the day shift, the cell software automatically exchanges the pallets to be loaded next to keep the cell in production as planned (unless the same pallet simply needs to be reloaded at once). As each open pallet arrives, the operator interface at the load station’s control panel enables the operator to open part loading instructions with photo illustrations, setup sheets and work instructions. Operator input tells the system the status of each pallet as it is loaded or unloaded. The system, in turn, manages pallet flow according to the schedule.

Mr. Hogoboom warns that it would be easy to underestimate the importance of these preliminary steps in the overall management of an automated machining cell. The software in the Fastems cell control system, however, rewards this effort by making cell operation smooth and efficient. “The proof is in the productivity of the machines in this cell—the only time they are not making chips is when pallets are being exchanged or cutting tools are being renewed,” he says.

A Model for Shop Management?

One other aspect of the cell control system not to be overlooked is that it serves as a machine monitoring system. It collects information about machine utilization, process details, alarms and alerts as they occur, and other data. This data can be analyzed and summarized in a variety of reports customizable by the cell leader and production managers. It is associated with individual part numbers for tracking and traceability purposes as well.

In fact, Mr. Hogoboom sees this automated cell as a model for how he would like the entire shop to function. For example, the degree of automation in the cell makes it very productive. Machining assets are utilized at a very high level. The cell keeps labor costs down yet maximizes the value of labor input. (P&J successfully attracts talented apprentices because positions with the company can be truthfully characterized as both good jobs and engaging opportunities. Supervisors keep their eyes on the best candidates to steer them toward an automated cell team.)

The cell control system also provides visibility. Shop managers can see where every job stands and how closely progress is adhering to schedule. There is no guesswork. Shop-wide visibility of this nature is difficult to attain.

The flexibility of the cell makes it ideally suited to the aerospace job shop environment. It supports responsiveness to customer needs, a capability that clearly distinguishes one parts supplier from the crowd. Dynamic scheduling is a major contributor to this capability, and one that Mr. Hogoboom would like to see matched by the entire manufacturing enterprise at P&J.

The pallet system serves two Matsuura H Plus-500 horizontal machining centers. These four-axis, 50-taper machines have 320-station tool magazines, high-pressure coolant systems and high-capacity chip conveyors that feed large chip bins.

https://www.mmsonline.com/articles/pallet-system-software-boosts-cell-flexibility